89. Rain and the new moon

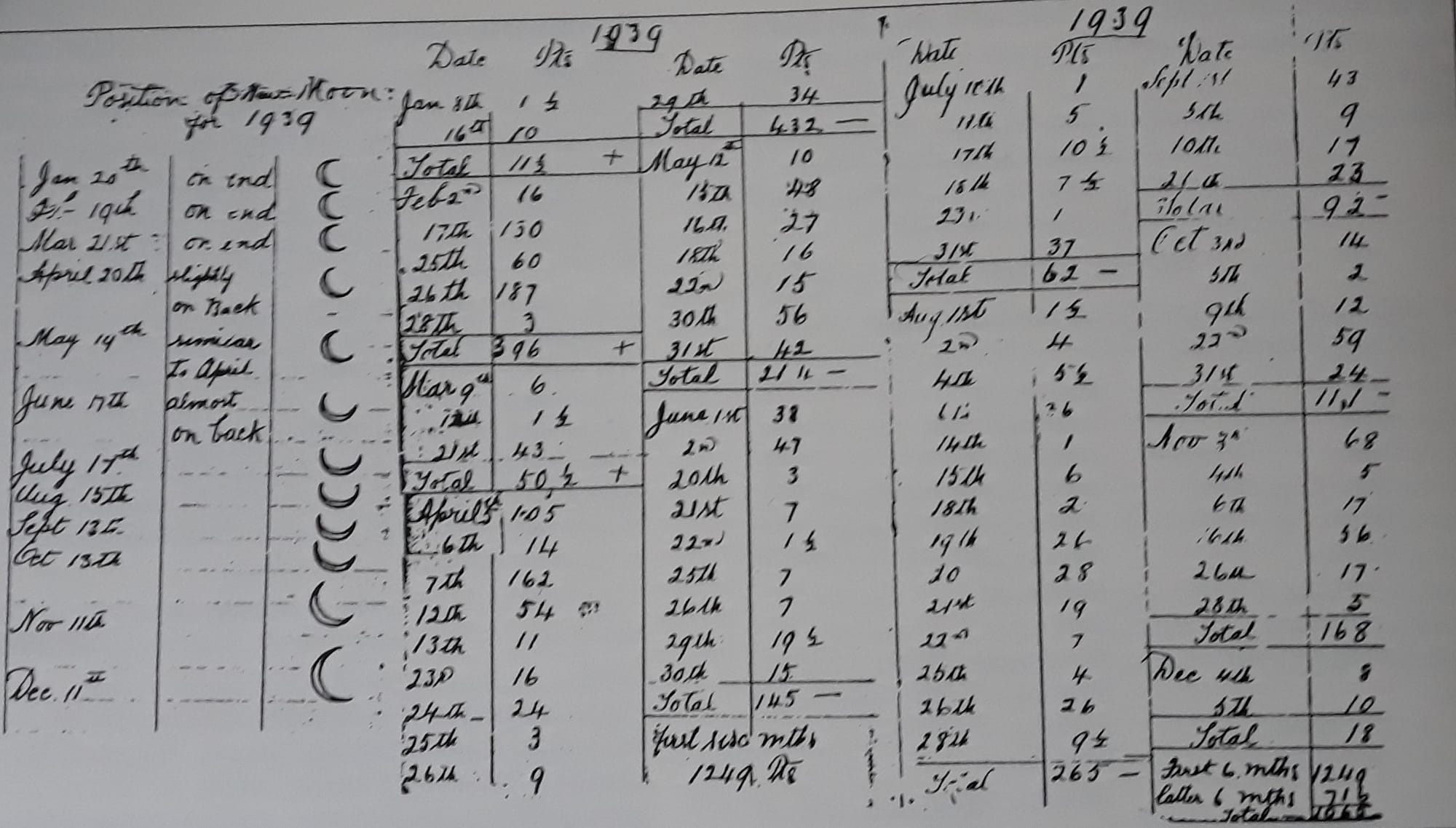

Just prior to World War 2, a farmer at Prairie, west of Rochester, recorded the rainfall on his property. At the same time, he sketched the position of the crescent new moon each month. He seems to have been testing a theory that there is a clear relationship between the position of the new moon and the amount of rainfall you could expect at that time of year.

The theory went something like this: if the new moon was in a near vertical position, you could expect that there would be more rain. If, however, the moon was on its back, looking like a saucer, there would be less rain. Based on the farmer’s amateur observations, it seems that the theory was correct when applied to 1939. There was much more rain in the months of the year when the new moon was in, or tending towards, a vertical position.

This raises the question of whether there is any scientific basis for what the farmer observed. It turns out that there is a sound basis for this in modern day science which had its origins in the ancient past.

TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE

Perhaps the farmer had been talking to local Aboriginal people because the traditional custodians of the land were all over what was happening in their sky Country. It was very important for them to understand the seasons, climate and weather and a range of tools were employed to assist them in this task.

They paid particular attention to the phases and position of the moon, as viewed from their Country. This is probably unsurprising, given that the moon is the most obvious feature in the night sky, with its appearance changing constantly as it goes through its regular 29.5 day cycle. Everyone is familiar with the full moon. However, we tend to take less notice of the position of the moon as it is waxing and waning, and in crescent, quarter or gibbous phases of partial illumination.1

CRESCENT MOON

The Prairie farmer’s depictions of the moon were recorded each month just after the new moon. At that time, the moon is at the start of its waxing phase (i.e. growing in size a little each night) and appears as a crescent – a depiction we are all very familiar with. The two pointy ends are called lunar cusps.

Torres Strait Islanders use “the orientation, or tilt, of the cusps…to signpost the seasonal arrival of the wet and dry seasons…The tilt is measured relative to the horizon.”2, which is exactly what the farmer was doing. When the cusps are pointing straight up, the crescent moon is like a saucer – it holds water and indicates the start of the dry season. The wet season is presaged when the cusps are pointing to the right. In addition to this, the phases of the moon help the Meriam people to determine the best times for fishing, important in a culture where fish is the staple food.3

Indigenous people who live near the sea also have a good understanding of the effect of the phases of the moon on the tides, using that knowledge to their advantage.

SCIENCE BEHIND LINKS

The connection between moon phases and the climate is not just some fanciful speculation. There is solid modern science to back it up. Observations and recording over the last few hundred years confirm that information handed down over tens of thousands of years by the traditional custodians is accurate.

It makes you wonder what initiated the Prairie farmer’s observations. Perhaps he had contact with remnants of the local indigenous people who passed the knowledge on to him. In the Waranga area, there would have also been a vast body of knowledge about sky Country that disappeared in a wisp of smoke in the 1830s and ‘40s with colonisation. That knowledge could have provided useful insights to present-day farmers and perhaps provided some forewarning of the growing issues related to climate change.

References: 1 Noon, Karlie & De Napoli, Krystal, Sky Country, Book 4 in a series on First Knowledges (Thames and Hudson, 2022) p 89-90; 2 op cit p 91; 3 op cit p 92