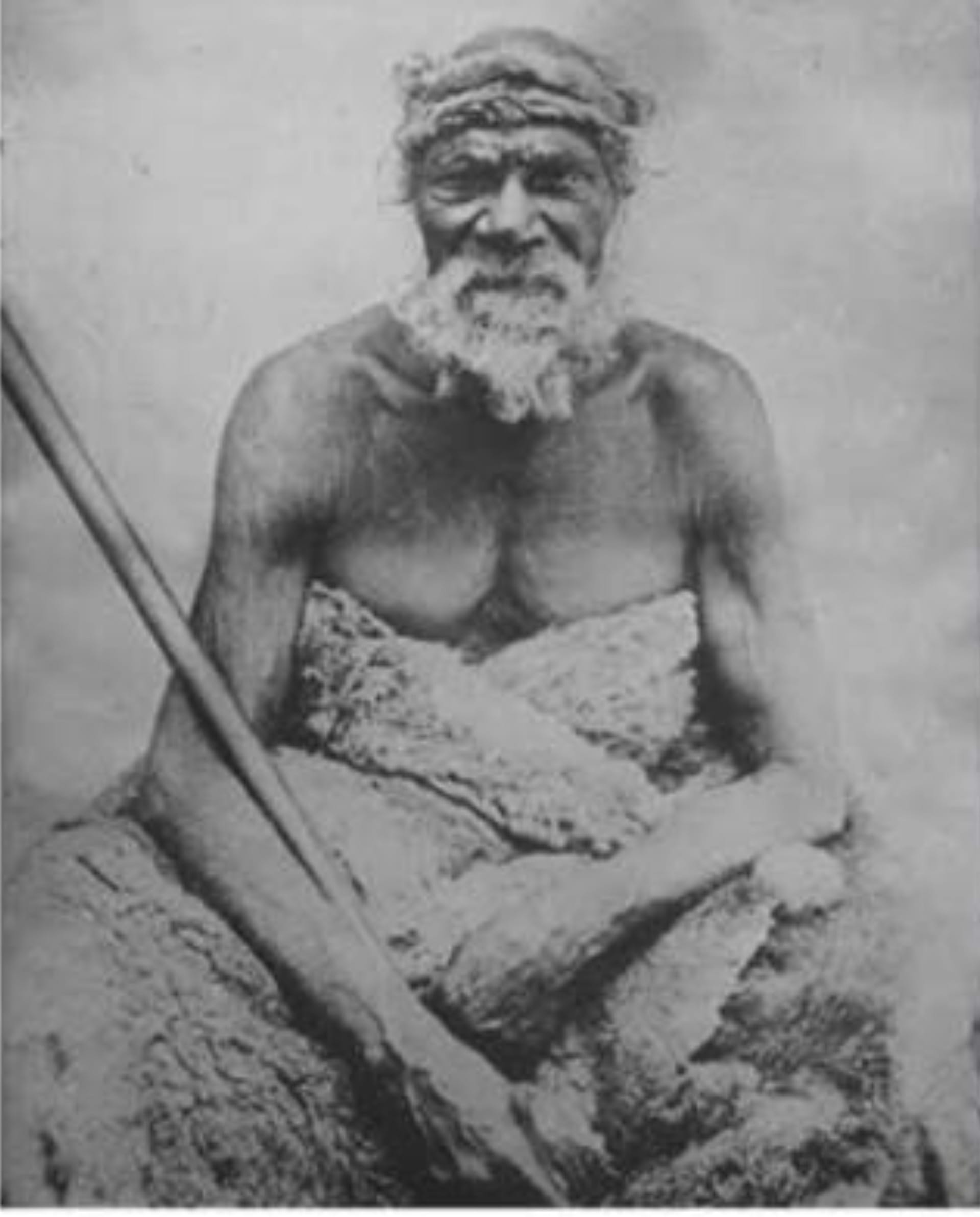

30. Tattambo – Ngurungaeta

Possibly the best-known 19th century Aboriginal person from this area is the man usually referred to as “King Charles” Tattambo, who died in 1868 and is buried at the Murchison cemetery. He had lived right through the period of European colonisation and witnessed monumental changes. There are a number of photographs of him, which is rare for Aboriginal people of this area. Many of them were gone before photography became commonplace.

It was standard practice back then to give Aboriginal people a European moniker, and the generations that followed Tattambo went almost exclusively by non-Aboriginal names.

BREAST PLATES

Part of the reason that Tattambo’s grave is so well-known is that there is a replica of his breast-plate on an iron fence surrounding the grave. The breast-plate was made of brass, featuring the words “Tattambo King – Property of Mr Fryer, Molka Station”. Molka Station was east of the Goulburn River and south-east of Murchison – part of Ngurai-illum Wurrung county.

The wording on the breast-plate seems to be a fairly sad indictment on the way that European colonisers saw the local Aboriginal people. Surely “property of” is tantamount to considering someone to be a slave? The wording is even more demeaning when you realise that Tattambo was a head man of some importance to the Ngurai-illum Wurrung people.

The term “King” used on the breast-plate is inappropriate, as it was not a term used by Aboriginal people. “King” implies that someone has absolute power, and may be entitled to hold the position on a hereditary basis. That was not the case in the structure of local Aboriginal communities. These days, it could also be interpreted as being used in a condescending, mocking way by the squatters, rather than as a term of respect.

NGURUNGAETA (pronounced Na-Run-Getta)

In his later years, Tattambo was a Ngurungaeta, or head man/elder for the Ngurai-illum Wurrung people. “The clan heads…were important figures…However the clans were never dictatorships, and decisions that affected the clan were only ever made final after extensive consultation amongst members of the clan. This democratic method and lack of hierarchical structure was unusual to the early white settlers who documented the first contact with Aboriginals.”1 This view adds further weight to the idea that “King” was inappropriate terminology.

Another discussion of Ngurungaetas says that “These individuals were men of distinguished achievement who had effective authority within their clans and 'were considered its rightful representative in external affairs'.”2 Distinguishedachievement” in large part related to the extensive cultural knowledge and history of the clan that was carried by the Ngurungaeta.

EARLY DAYS

Tattambo was born into the Gunung Willam clan, which was based on the Campaspe River. This was about as far away as you could get in Ngurai-illlum Wurrung country from Molka, so it is an inaccuracy to say that Tattambo was “of the Molka Tribe”. After the dispossession caused by European colonisation, clans lost their traditional country, which could account for Tattambo finishing up at Molka. Perhaps he worked on the station, which was a common role for Aboriginal people in colonial society.

The moiety of the Gunung Willam clan was Waa, the crow, which would have been an important totem for Tattambo, along with anyone else born into that clan. We don’t know exactly when Tattambo was born, other than that it was in the very late 18th or early 19th century, well prior to first contact with Europeans. One oral historical account from an old Murchison resident3 suggests that the first white man seen by Tattambo’s young son (and Tattambo?) was when Major Mitchell’s expedition passed through the area in 1836.

So, although we know almost nothing of Tattambo’s early life, it is not hard to imagine him growing up in the safety and security of Ngurai-illum Wurrung clan life, gradually building the knowledge and skills that would prepare him for his later life as a Ngurungaeta.

References: 1 http://heritage.darebinlibraries .vic.gov.au/article/643;

2 https://www.vaclang.org.au/languages/ woiwurrung.html; 3 Waranga Chronicle 29.10.1874 (Thanks Alan McLean)