2. Born on the goldfields

The man who was the inspiration for these stories was apparently born in High Street Rushworth in 1855-6. There are contemporary reports of groups of Aboriginal people camping at the bottom end of High Street, and at least one reference to a corroboree being held there.

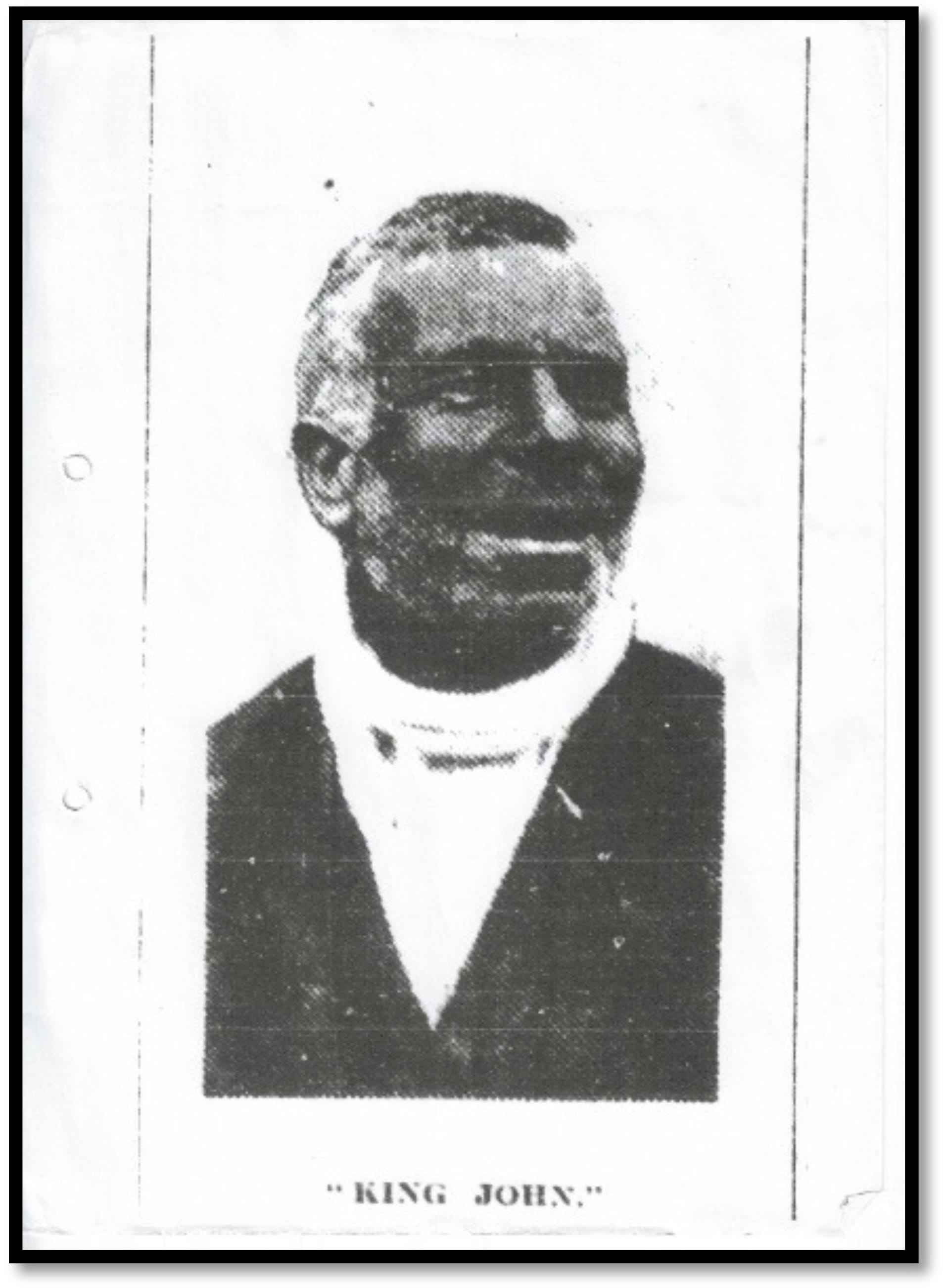

To put his birth into context, this would make the man, later known as “King John”, one of the first children to have been born in the new town. The overwhelming majority of Rushworth residents at the time were single men, intent on pursuing their dream of striking it rich on the goldfields. Families, and the birth of children, would have been quite rare at the time.

Many Aboriginal people had been displaced since squatting began in the 1830s, and by 1855-6, the Aboriginal Protectorate at Murchison had already been disbanded. Moving to the vicinity of a new mining settlement provided a range of economic opportunities for the Aboriginal people who remained in the area.

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND THE GOLD RUSH

In the histories written about the Victorian goldfields, Aboriginal people are generally given scant recognition. Fred Cahir rectified this to some degree with his 2012 publication, Black Gold – Aboriginal People on the Goldfields 1850-1870.

The book shows that one of many roles that Aboriginal people fulfilled was to provide a reliable labour force for the by-then well-established pastoral industry, when many of the existing workers had gone off to the gold rushes. Our King John “spent some strenuous years in the Avenel district, breaking in horses and shearing.” Perhaps this line of work was what some of his forebears had done in the 1850s and beyond.

ROLES IN GOLD MINING

Apart from working in the pastoral industry, Fred Cahir cites many examples of Aboriginal people seizing the opportunities provided by the gold rushes to make a living. Certainly, there is evidence to suggest that Aboriginal men engaged in mining. The value of the precious metal to the new arrivals was recognised, even though it was not necessarily valued by the original custodians of the country.

The story that is usually told about the start of the Rushworth gold rush revolves around an Aboriginal woman showing travellers where gold could be found in what became Main Gully, just south of the town. These travellers were camping, while on their way from Bendigo to Beechworth goldfields, when they noticed the countryside looked similar to that around Bendigo i.e. ironbark forest, gravelly hills. After showing the local Aboriginal people some gold, the party was directed to places where alluvial gold could be found nearby.

OTHER ROLES

Aboriginal people around Rushworth in the 1850s were also able to compensate to some extent for the loss of access to country by providing goods and services to the new arrivals. Fred Cahir concludes in his study that “many Aboriginal people sought to find their niche in the new society, via predominantly economic channels, through trading in their manufactured goods, farming and cultural performances, or in employment roles such as bark cutting, tracking, guiding and police work, which did not inordinately compromise their cultural integrity and took advantage of their superior traditional work skills”.

Later in life, our “King John” certainly followed in this tradition, making a living by manufacturing and selling boomerangs, and giving exhibitions of boomerang throwing.

An article in the Melbourne “Herald”, which resulted from an interview with King John in 1913, states that he was a member of the “Woorung” tribe. Perhaps this was an abbreviation of the name of the Aboriginal people who for millennia had frequented what became the Rushworth area – the Ngurai-illum Wurrung.

References: Melbourne Herald 3.10.1913; Cahir, Fred, Black Gold – Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Victoria 1850-1870 (ANU E Press 2012)