2. Chinese gold miners

During the 19th century gold rushes, many Chinese miners came to the Waranga area, mostly from the mid-1850s onwards. In history, they have tended to be lumped together into one homogenous group. One reason for this was that they tended to stick together as part of tight-knit groups because of the opposition from European miners. However, with such large numbers involved, there was great diversity across the group that generally went unrecognised by many observers.

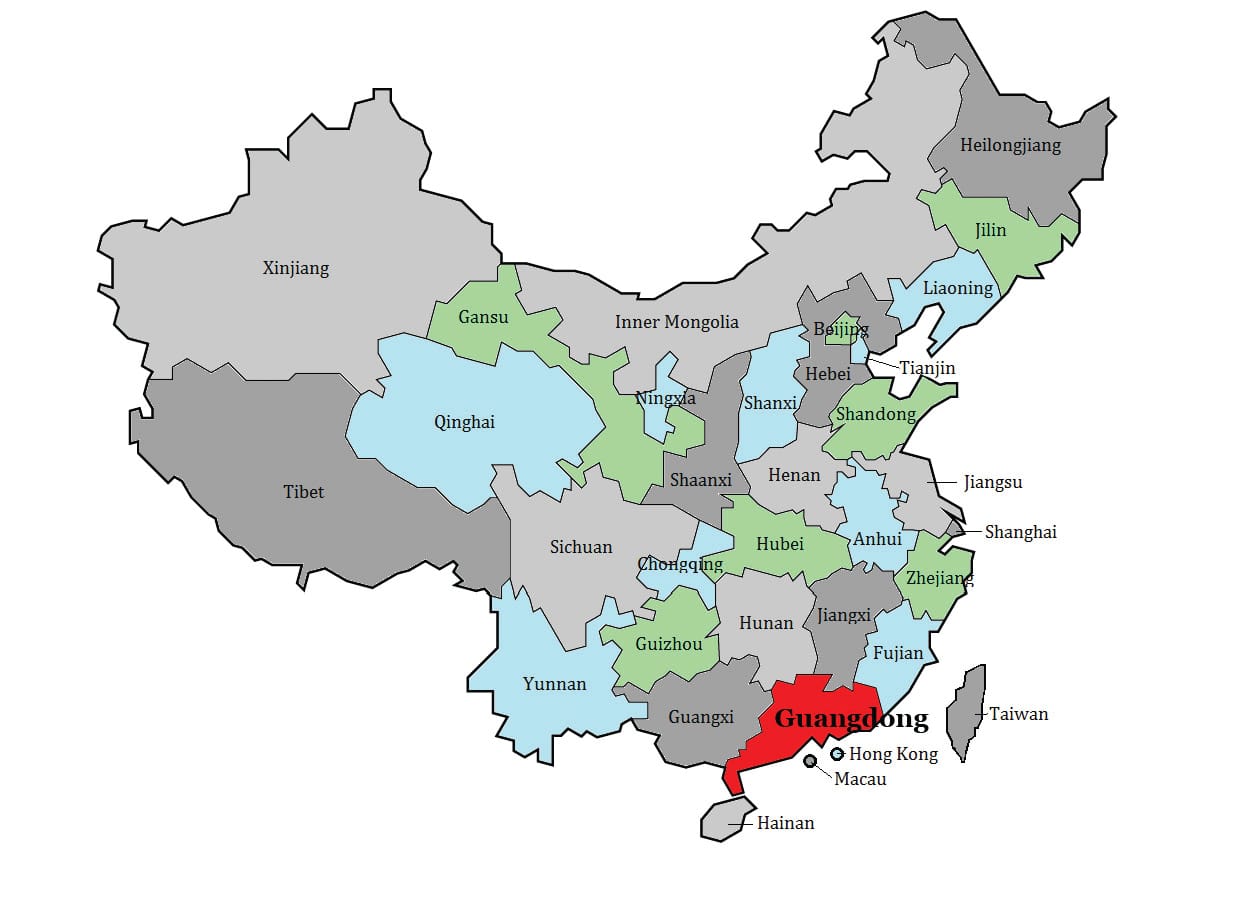

Most of the local miners (an estimated 90%) came from Guangdong province, which is a coastal province in the south-east of China, bordering Hong Kong. At the time of the Australian gold rushes, there was turmoil in China (foreign incursions, political instability, population pressures, famine, natural disasters) and great poverty in that part of the country. That made the prospect of going overseas to find gold an attractive proposition. Gold was highly valued in Chinese society.

Most of the miners were men, with only an extremely small number of Chinese women coming to the Australian colonies. The men who came generally had a strong spiritual, cultural and family connection to China which meant that in time, many expected to return to their country of birth. For those who died while in Australia, there was a hope that their earthly remains would be repatriated. Given the circumstances of the gold rush, this was a vain hope for many. Locally, this resulted in some Chinese burials in Rushworth, Whroo and Murchison cemeteries.

HOW DID THEY COME?

Many of those who came to Victoria to the gold rush were from a region known as See Yup, or the four counties, 100-200 kms south-west of the provincial capital of Guangzhou (known to Europeans as Canton). Smaller groups came from other areas and there were “at least 14 different dialects spoken by Chinese voyagers to Victoria in the 19th century, reflecting their diverse home villages and cultural backgrounds.” People from different parts of China were not always on good terms with each other and sometimes those antipathies came with them.

Most gold seekers from Guangdong province began their journey to Australia by walking or riding to the provincial capital. The many river crossings and some of the travel would have been made on vessels known as junks. Larger junks would then ferry them to a seaport such as Hong Kong, where they would wait in shanty towns for British, American or Dutch sailing ships heading for Australia.

On arrival, the miners would then have to walk to the goldfield of choice. Victoria introduced a prohibitive entry tax in late 1855 which meant that many landed in South Australia or New South Wales to avoid the tax. However, they then had to do an epic walk of hundreds of kilometres before they could start work.

CONTRACTS

Some miners used their own resources to migrate, but many were too poor to afford the cost involved. In those situations, organising companies recruited miners and contracted the workers. The companies would pay for the passage to the goldfields, with the miners obliged to repay the loans with interest. This could be problematic as there was no guarantee of success on the goldfields.

Often, as part of the contract, the workers would be required to be part of “controlled and well organised teams with special subdivisions (miners, cooks, interpreters etc) under a team manager, or a ‘headman’, until they had worked off the debt.” Once this had been done the workers were free to mine for themselves or go into other businesses using the proceeds of their earlier mining activities.

BACKGROUNDS

As discussed, there were very few Chinese women who came to Australia, largely for cultural reasons. The men were mostly aged between 20 and 40 and were from a wide range of backgrounds – not just agricultural peasants. “Miners, carpenters, translators, entertainers, scholars, gardeners, butchers, cooks, doctors, herbalists and entrepreneurs were in their midst” and many were literate. China had a comparatively advanced education system at the time.

About a third of the Chinese men were married, which made returning to wives and families in China a priority (or not in some cases!). Some who stayed in Australia married European women, but this was uncommon because of a relative dearth of women in gold rush societies.

Ref: https://victoriancollections.net.au/stories/many-roads-stories-of-the-chinese-on-the-goldfields/voyaging-to-australia